Is Gender Bias Still At Play

Julia Harris

Sunday, 4 September 2021

Division 5 AFLW player Teearna Dios-Brun became interested in football “because every weekend I would go and watch my partner play.

I always thought that football was a sport for men because I never even saw anything different on TV,” Teearna explains. Women have always been delegated to the sidelines. Females who resist, are called difficult and problematic as women are expected to know their place in society”.

Australian Rules Football, otherwise known as the AFL, football, or footy, is an Australian multibillion-dollar entertainment and sporting industry that’s closely guarded by men. They are the experts as its their sport and they’re the ones who created it, and who play it.

The AFL, the Seven Network and Foxtel, with the government facilitating the sport’s infrastructure, package the sport for our weekend entertainment. The commodification of football shapes our reality and guides our perceptions of Australian culture. It’s also a sport that no woman would ever be expected to participate in. This ideology has been ingrained into our culture for generations.

However, a persistent push by females against social norms, has ricocheted over the past twenty years, onto the Australian sporting landscape, and found itself changing the sacred AFL.

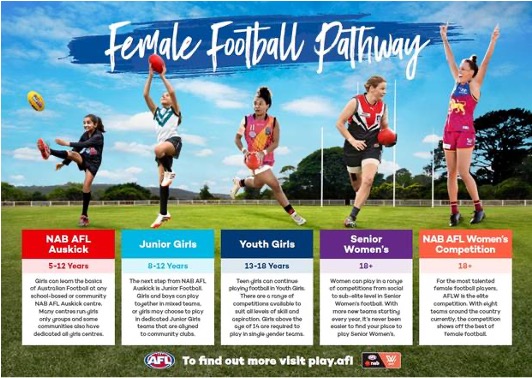

It began when the AFL first established Vickkick in 1985 within Victoria, and then Auskick nationally in 1995, to target children of both genders aged from five years to twelve. The program encouraged participation in football, to promote the AFL.

The female player age limit however, dictated by AFL’s The Female Participation Regulation, ruled that girls could not continue to play football after twelve years of age. This was challenged in 2003 by two Victorian girls, who argued the Regulation conflicted the Equal Opportunity Act (Victoria). Consequently, the AFL replaced the Regulation with the Gender Regulation Policy (Section 4) allowing girls aged up to age fourteen years to play. Though, yet again, girls aged over fourteen years were excluded from participation.

Fast forward to 2017 and the AFL established the AFL Women’s (AFLW), after an amplified growth in interest of females who wanted to play the sport.

Source: aflcommunityclub.com

The AFLW is a tangible example of equal rights that females seek. In a momentous realisation, Teaarna excitedly says “I now strongly believe that women can play any sport that men can and do just as much as what men can do.” The visibility of female role models as both players and within commentary positions coincide with movements such as #MeToo that propel women’s rights and allow girls to dream big.

However, the game’s soul has been built on the back of tradition that originated 150 years ago, when the game was created as a space for men to release the hardships of the day, both as a spectator and player. It was a place where men could voice their emotions, among the gathering of like-minded communities. It was essentially, as a game for men.

In consideration, there is strong opposition and emotional reactions from men when changes to the game’s traditional rules occur, and when the game’s soul is seen to be under threat. In 2019, an image captioned, “Photo of the Year” of Carlton AFLW player Tayla Harris, was posted on the 7AFL Twitter account. The striking image attracted derogatory and sexualised comments and in response was hastily deleted. After enormous backlash, the image was re-posted with an apology and was replicated as a statue at Federation Square in Victoria, to symbolically represent women’s rights to play in the game. However, substantial opposition from high profile ex-players and coaches, for example, ex Crows Coach Malcolm Blight, questioned the statue’s suitability and worthiness, highlighting that many other male legends are bullied online and not represented.

(Source: TheGuardian.com)

Attaining equality in the AFL cannot be based solely on a female’s right to play. Even though females have reached permanent residency within the AFL, they are paid considerably less than men. Therefore, they work alongside their football obligations with less time to hone their skills.

An additional issue is the female skill level is not equal across all players. Many female players cross over from other sports, or from highly coached sporting backgrounds. With a superior level of skill, they can separate themselves from their team-mates, and become publicly recognised. For example, Crows AFLW player Erin Phillips, is a former Olympian and basketballer, and Tayla Harris, a former boxer. Inferior skills can be directly attributed to the limited infrastructure and high-level training while girls were growing up. The AFLW, therefore, will not reach its full potential until younger female generations with appropriate gender-based training facilities, amenities, and support, move through the system from an early age.

Importantly though, the photo and statue of Taylor Harris will forever be immortalised as a metaphor for equal rights and for females to be seen for what they do, rather than what they look like, or what they should be.

Media enquiries:

Julia Harold, Communications

Max Amber Sportsfield Hub

m; 0000 444 333.

e: abc@abc.com